An example from the mainland

The region of North Jutland (Denmark) around the city of Aalborg and the AAU Aalborg University, with inputs from industry and other stakeholders, recently have decided to start a number of “Mega Projects” in order to realize the UN SDG Goals. The umbrella projects aims at significant societal change, in which always one or more of the 17 SDG Goals are addressed, over a more-year planning. Knowledge-action-networks are the core of the program, in which collaborative communities engage in themes critical to local and globalsustainability. The first two Mega Projects themes are: The CircularRegion and Simplifying Sustainable Living. Both Mega Projects have been commissioned by Aalborg Municipality. For instance the Circular Economy project includes the following:

- Concretizing activities to be undertaken in the municipality and in the region;

- Identifying actual opportunities and solutions for slowing, closing and narrowing resource loops; e.g., how to design for reuse, disassembly and recycling, or how to ensure collaboration between different stakeholders, sectors, anddisciplines, including all curricula of the five AAU AalborgUniversity Faculties.

Source: Stoustrup, 2019

Example of strategy 5B:

Working with the UN SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals)

When developing your local or regional vision, it makes absolute sense to take the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as points of departure. With 17 goals and 169 sub goals and a similar large amount of indicators the endeavour seems at face value quite bureaucratic and a mission impossible. However, these challenges can be overcome by a smart, efficient and well planned local or regional program.

The attractiveness of the UN 17 SDG Goals is that they involve a holistic approach, with comprehensive, global values: social aspects like poverty, inequality, cultural values, education facilities, gender issues etc. are considered equally or even more important than “classic sustainability” aspects, such as environmental impact and economic viability. (Reubens, 2016). Therefore, frontrunners among countries, regions, cities, companies, universities etc. are quite active in adopting the UN SDG Goals, discussing what the consequences are, how the goals in an concerted action by all stakeholders can be realized and who can contribute what over time.

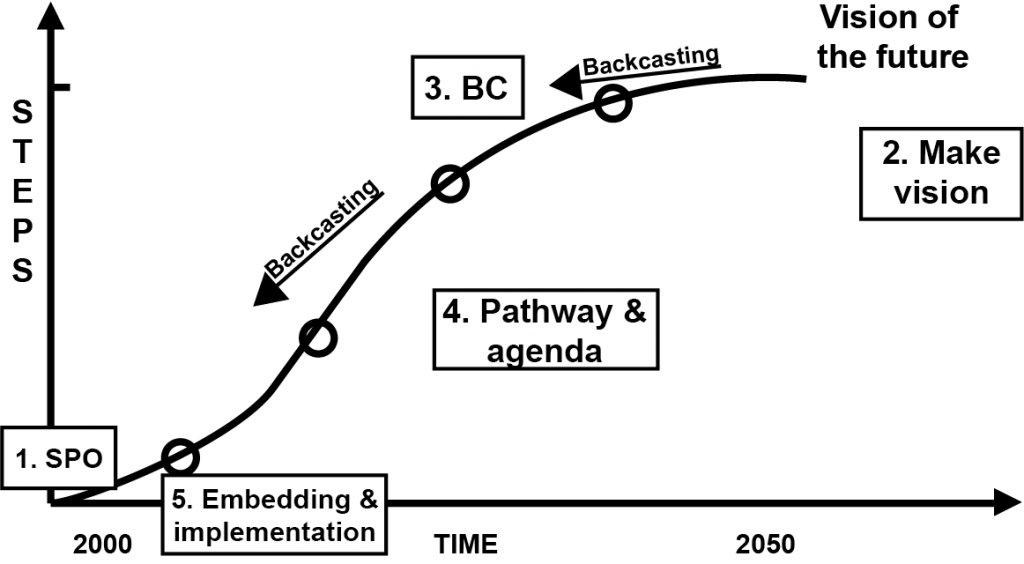

Joint regional programs are designed in such a way that the SDG Goals are integrated in larger themes and tasks are divided over time and between stakeholders, to increase the feasibility. It is absolutely clear that public municipalities and regional entities, as close partners of the national government, have a special responsibility for these initiatives and should adopt a facilitating role in developing a local or regional SDG program on their island. Such a process could go very well hand-in-hand with the approach described above, regarding using Backcasting scenario’s for vision development.

More info: UN, 2017. The Sustainable Development Goals 2017. United Nations, New York, USA.